Modest Conceptual Functionalism, Distilled

As I work on cleaning up and finishing my dissertation, I’m creating ‘distilled’, snack-sized versions of each chapter. I hope this helps me: a) see the ‘big picture’, b) get high-level feedback from more people, and c) entice people to read the real thing.

This post distills “Making Room for Modest Conceptual Functionalism”.

When we talk about ‘what it feels like’ to be in some mental state, we use phenomenal concepts. When we talk about causal architecture, we use functional concepts.

The main question I want to look at: How are phenomenal concepts related to functional concepts?

I find it useful to think about this question in the following way: Imagine we have two lists. On one list, we have every possible phenomenal description. On the other list, we have every possible functional description. We can answer our original question by answering: which functional descriptions can be read off which phenomenal descriptions, and vice versa?

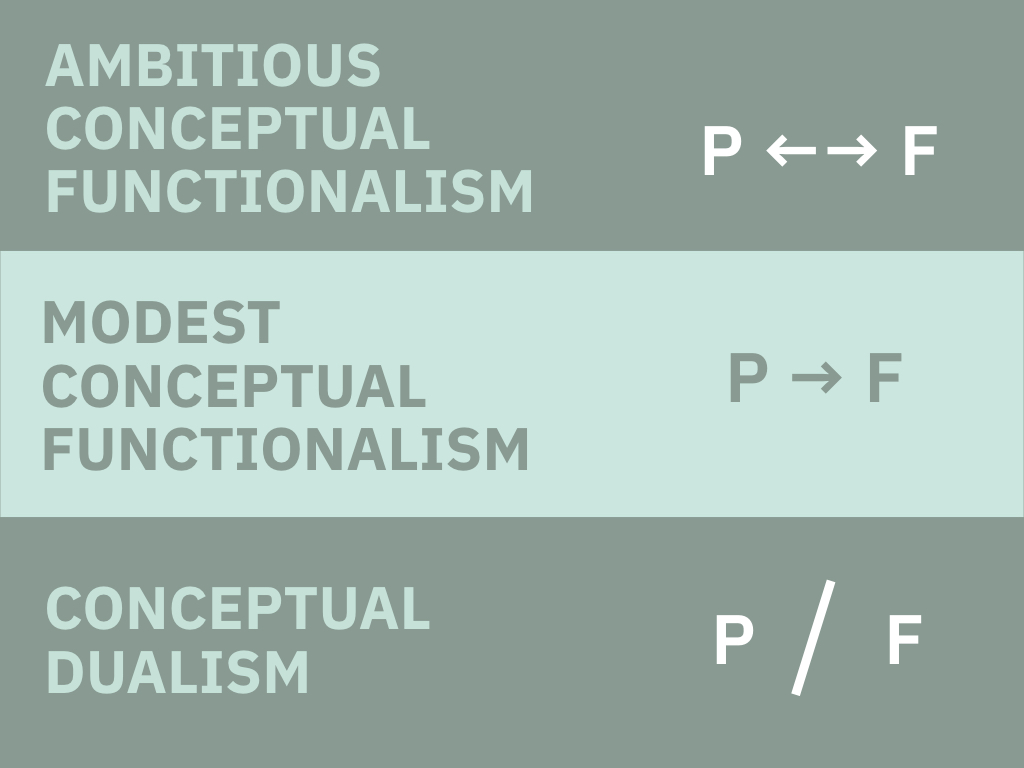

Different answers, then, will map onto different ways of mapping out the entailments linking these two lists:

With that model in mind, I want to give a high-level sketch of the space of possible views.

At one extreme end of possible views, we find:

- Ambitious conceptual functionalism: for every phenomenal description, there’s a matching functional description that both entails it, and is entailed by it.

This view has two big problems: absent qualia and inverted qualia. Such cases seem to show that, as a conceptual matter, phenomenal descriptions ‘say more’ than mere functional descriptions. (In particular, absent qualia cases show that functional descriptions can’t settle whether some system is phenomenally conscious, and inverted qualia cases show that functional descriptions can’t settle the precise character of consciousness when a system is phenomenally conscious.)

And so we might be attracted to the other extreme end of possible views:

- Conceptual dualism: The phenomenal is conceptually independent of the functional. Phenomenal descriptions don’t entail functional descriptions, and vice versa.

In my estimation, too many philosophers have embraced conceptual dualism—whether or not they fully realize it. You’ll regularly encounter claims like these, from Brain Loar’s “Phenomenal States”:

- “Phenomenal concepts are conceptually irreducible in this sense: they neither a priori imply, nor are implied by, physical-functional concepts.”

- “Phenomenal concepts are conceptually independent of physical-functional descriptions…”

That is, they elide the conceptual irreducibility of the phenomenal to the functional with a sort of conceptual independence. A much better option is:

- Modest conceptual functionalism: Some phenomenal concepts have built-in functional constraints. So while functional descriptions don’t entail phenomenal descriptions, at least some phenomenal descriptions entail functional descriptions.

Modest conceptual functionalism, as a category, covers any view that eschews functional-to-phenomenal entailments but embraces some form of phenomenal-to-functional entailment. But which sorts of functional constraints on phenomenology are plausible? Where should we look?

I see two promising sources:

-

Subject-based constraints: The idea of a phenomenal subject might contain within it an idea of how phenomenal subjects have to be structured, in functional terms. The possibility for such a constraint is hinted at in the way absent qualia cases are constructed: it’s telling that we first need to identify candidate experience-havers before we then go about subtracting their phenomenology. Pursuing this line of inquiry will, I think, reveal that phenomenal subjects have to implement a kind of working-memory-like structure. (Strange experience cases can, I think, be used to uncover such constraints.)

-

Phenomenal-kind-based constraints: Different phenomenal kinds (e.g. color experience, auditory experience) might, necessarily, meet kind-specific functional constraints. The possibility for such constraints is hinted at in the way inverted qualia cases are constructed: it’s telling that we think red experience/green experience phenomenal swaps are, intuitively, more intelligible then, say, red experience/anxiety phenomenal swaps. Pursuing this line of inquiry will, I think, reveal that the structure of phenomenal variation for each phenomenal kind has to be matched by the structure of functional variation in any underlying state. (Dissonant qualia cases can, I think, be used to uncover such constraints.)

Why does this all this matter? Why care about conceptual dualism vs. modest conceptual functionalism? Two big reasons:

-

The intelligibility of physicalism: Even if physicalism isn’t true, it at least seems like an intelligible view—more intelligible than the view that phenomenal consciousness is the rate of economic growth in Bulgaria. Modest conceptual functionalism can make sense of this intelligibility, while conceptual dualism cannot.

-

The tractability of a science of consciousness: If conceptual dualism were true, it would make a science of consciousness impossible. Confronted with two different hypotheses about the actual correlation between phenomenal properties and functional properties, we wouldn’t know how to bring objective, third-personal evidence to bear on this issue. Even if there aren’t any entailments from the functional to the phenomenal, we could still use phenomenal-to-functional entailments to help provide ‘guardrails’ for our empirical project.

Other Dissertation Posts:

For discussion…